The screw arm plow plane is one of the most iconic wooden planes. They're beautiful, the fever dream of a hyperactive woodworker. "How is it," asks collector Don Rosebrook, "that such a simple tool, designed to make a cut that, under normal circumstances, no one would ever see, became the most elaborate, most expensive, often gaudiest, woodworking plane that the makers would produce?"1

Cutting a long groove to a uniform depth with a chisel is time consuming. By the time of the Romans, woodworkers had figured out that they could simplify the task by fitting a chisel in a block of wood to make a simple grooving plane.2 (Rex Krueger has plans if you want to make your own.) Each subsequent advancement, each iteration of that tool gave woodworkers a little more control. A depth stop determined how deep the groove was. A skate allowed the use of irons of various widths. A fence ensured the groove was always parallel to the edge of the board. And so, slowly over the centuries, the plow plane was born. By the mid-1500s the English (and likely the Dutch)3 and Germans4 were using them.

One of the biggest innovations was the screw arm. Not only did the screws allow for easier adjustments to the fence, the knobs and nuts lock the arms in place. While people have been making wood screws with helical threads for more than 2,000 years,5 the earliest known screw arm plows were collected by the aristocracy in the 1570s in Germany.6 Their basic design – with arms attached to the body of the plane, and a fence that slides back and forth on the arms - would remain unchanged on the continent for hundreds of years.

Surprisingly, screw arms didn't show up in England until about 1770.7 Why did the English ignore them for so long? We don't know. Maybe they didn't like the continental arm design. When plane makers in York made their first screw arm plows, they used a style that was already unique to English plows.8 Instead of the arms being fixed to the body, they slid through the body. It was a modification that would eventually allow for a better fence design and open the door for more significant improvements in the coming century.

Thomas Napier brought the idea across the Atlantic when he emigrated to Philadelphia from Scotland in 1774. He and Hugh Hazlet, who worked with Napier, were probably the first in America to make screw arm planes in about 1800.9 From the turn of the 19th century onward, (aside from a brief experiment with metal screws tucked inside plane arms) there were few changes to screw arm plows in England. Continental Europeans were stuck using their centuries-old design. Americans, on the other hand, got busy.

Keeping a plow fence parallel to the plane body has always been a problem. If you tap one arm further through the body than the other the fence goes out of line, even with screw arms. Eighteenth century American makers tried to overcome it by dadoing the arms to the fence. Philadelphia plane maker Israel White's 1834 patent for a three-arm plow – with two unthreaded arms holding the fence in place and a third threaded arm that moved the fence back and forth – was likely inspired by European designs but was the first American attempt at solving the problem of parallelism.

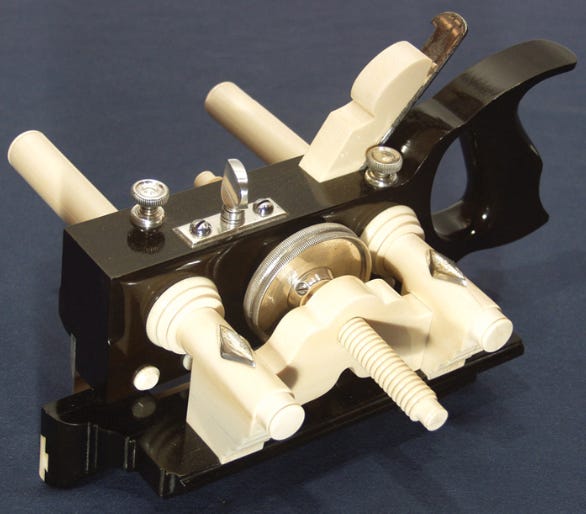

Whether it actually did is debatable, but it kicked off a long line of tinkerers – Henry White, John King, David Andruss, Mockridge and Francis, William Ward, Chapin and Rust – who experimented with the three-arm design.10 The final chapter in screw arm evolution was the addition of a large adjustment wheel, made of either wood or brass, to the center screw arm. Ohio Tool Co. made the first center wheel plane in the 1850s; another Ohio firm, the Sandusky Tool Co., also made them up until the 1920s.11

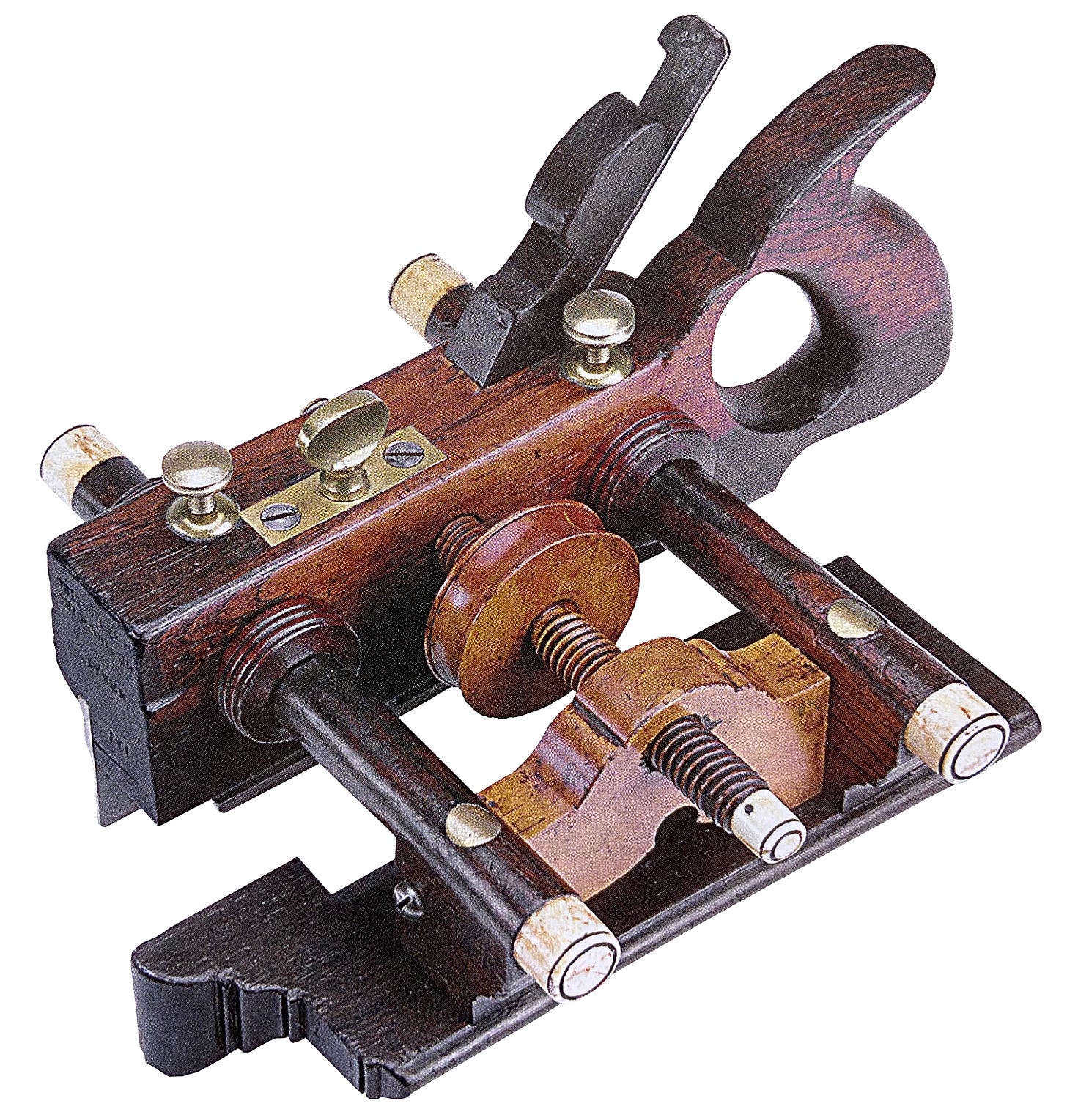

While American plane makers were experimenting with parallelism, they were also making their screw arm plows more ornate. They added handles and capped the ends of the arms with ivory. They used exotic woods: coccabollo, mahogany, boxwood, rosewood, even ebony. Ivory was also used for knobs and inlay. The most remarkable example is an ebony and ivory Sandusky Tool center wheel plow that was likely made to display at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.12 It's the pinnacle of the plane maker's craft. Pinnacles don't come cheap. It sold for more than $100,000 at auction in 2005.

Three-arm plows and center wheels never became the dominant style in America (their high cost outweighed their limited benefits). But double screw arms, despite being expensive, were still the most popular type of plow. By the late 1800s the major plane makers offered 20-30 types of plows; the vast majority were screw arm. Why pay more when a simpler plow that did the exact same job and was a fraction of the price? The European version with metal screws was much cheaper and easier to make.13 In America, the screw arm plow was a tool, but it was also a symbol: of a craftsman's pride in their work, of status in the workshop, of Americans’ belief that ingenuity was a sign of progress.

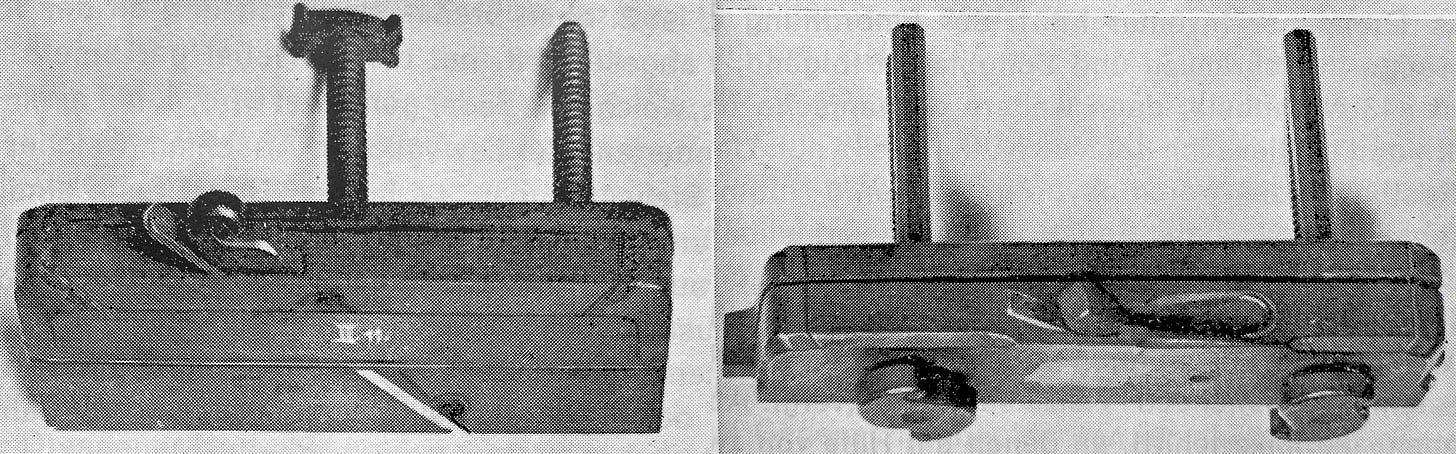

We're able to trace the latter evolution of these tools because commercial plane making – which began in the Netherlands around 1600, in England in the late 1600s, and in America as early as the 1720s – left a trail of planes stamped by their makers. We know much less about innovations in other parts of the world. Japan and China have a long history of plane making. They each came up with their own types of plows, including some with very short fences on a single arm secured by either wedges or a thumbscrew.14 We don't know what kind of ideas they discovered and discarded as they developed their unique designs.

As to who "invented" the screw arm plow plane, it could have been the Germans. But the planes that survive from the 1570s weren't invented then. It was an already established design. From the Renaissance to the 1800s, the development of new types of joinery and molding planes were entwined with the evolution of increasingly complex furniture, cabinetry and architecture styles. The desire for new styles prompted the development of new planes; new planes spurred the development of new styles. Each adaptation was built on a long line of adaptations.

Design is a living process, both iterative and recursive. Maybe in the world of tools there are no inventors, only adapters.

– Abraham

Polish plane maker Stavros Gakos’ videos are a joy to watch. Here he is making a screw arm sash filletster/fillister plane.

Jim Gehring from Brown Tool Auction shows off some of the plows on offer at their 2019 event, including a rare piggy-back plow by H.L. Kendall.

Paul Hamler, who makes incredible miniature woodworking tools, describes how he cuts wood threads, including tips on repairing damaged wood threads on plow planes.

Don Rosebrook and Dennis Fisher. Wooden Plow Planes: A Celebration of the Planemakers’ Art. Astragal Press, 2003.

Roger Bradley Ulrich. Roman Woodworking. Yale University Press, 2007.

Jane Rees. Goodman’s British Planemakers. 4th ed., Astragal Press, 2020.

Josef Greber. Die Geschichte des Hobels. 1956. Schäfer, 1997.

Jim Packham. “Threads in Wood.” The Chronicle, vol. 56, no. 2, 2003.

Greber, 1956.

Rees, 2019.

Richard Knight. "Two Early English Screw-stem Ploughs." Tools and Trades, vol. 1, 1983.

Carl Bopp. "From the Distaff Side: Some Female Entrepreneurs." The Chronicle, vol. 57, no. 3, 2004.

John A. Moody. The American Cabinetmaker’s Plow Plane: Its Design and Improvement, 1700-1900. The Tool Box, 1981. Herb Kean. “Three-arm Plows.” The Tool Shed, no. 107, 1997.

Rosebrook, 2003. Moody, 1981.

Christopher Schwarz. “Almost a Plane Wreck.” Popular Woodworking, April 2005.

Seth W. Burchard. "Austrian and American Plows Compared." The Gristmill, no. 47, 1987.

John M. Whelan. The Wooden Plane: Its History, Form, and Function. Astragal Press, 1993.

I never realized just how ornate and beautiful these plows could be! This glimpse into the overview of the development of this particular type of plane helps me gather a bit of perspective on why and how later plane makers who used cast iron would have used these planes as a model on which to innovate new designs. Thanks for sharing this!