Everything we know (and don't know) about dated Dutch planes

Plus, Walter Rose on the lineage of plane ownership

We hit 600 subscribers this month! I am so lucky to have such a passionate, engaged readership (nearly every issue has had a staggering 60%-70% open rate).Thank you, each and every one of you, for reading, commenting, and sharing this newsletter over the last two and a half years.

The ornately carved bodies, handgrips, and totes on early Dutch planes offer a glimpse into an era where little is known about commercial planemaking. Dates are typically found on what the Dutch call brede schaven, wide-bodied planes with a top escapement. (Plow planes are occasionally dated as well.) They weren't showpieces — many dated planes have been heavily used. While the earliest known examples were made in the mid-1660s, the majority are from the 1700s.

The carvings don't appear to be tied to specific planemakers. The researcher and author Gerrit van der Sterre has identified planes from the same maker with identical dates but with different carving styles. He guesses that the woodcarver, not the planemaker, chose the pattern.1

The carvings would only have been made by a professional woodcarver. The guild system of the time strictly regulated every type of woodworking. For instance, a house carpenter wasn't permitted to cut miters or make his own bedstead. In Bruges, Belgium, he wasn't even allowed to apply glue to his work. All of these were solely the purview of the cabinetmaker. The consistency and quality of the plane carvings are evidence of a specific, standardized skillset likely exclusive to a woodcarver.2

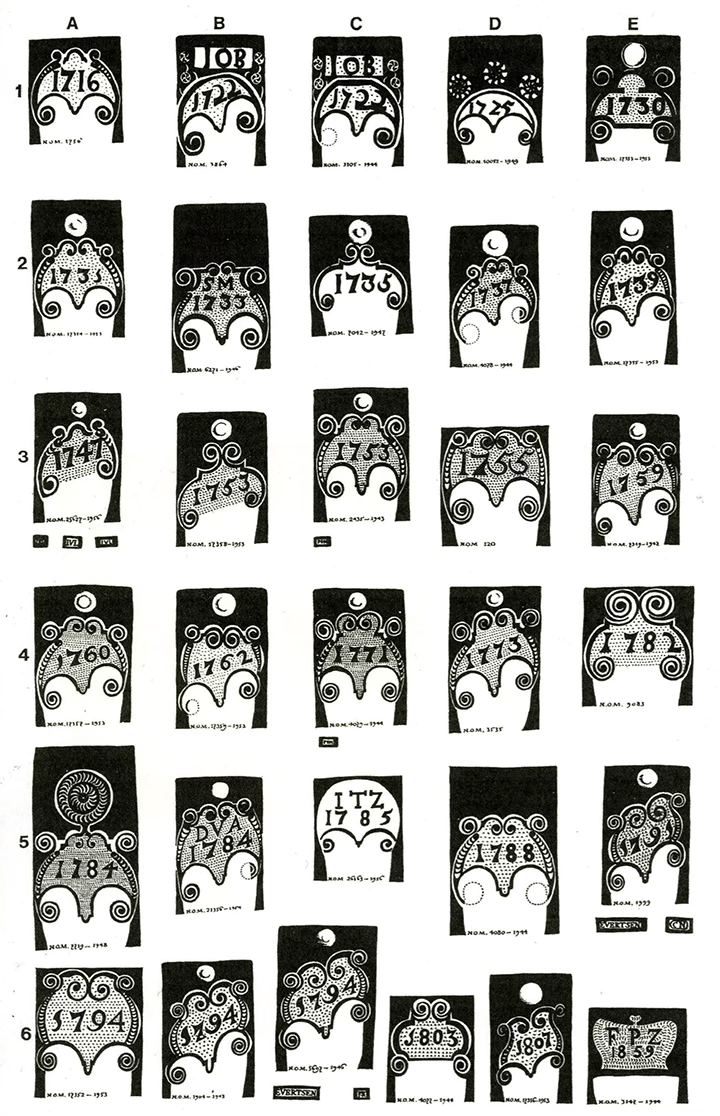

Several overlapping trends in the carving styles have been identified. According to Hein Coolen, former president of the Dutch antique tool group Ambacht & Gereedschap, type A (see chart below) is the earliest and is infrequent after 1740. Type B dates to before 1750 and eventually developed into type E, which occurred from 1730 onward. Type C, the most common, was in vogue from about 1725 to the end of the 18th century, followed by type D. The largest concentration of types C and E date to the middle of the century.3

With everything that's known about the carvings, the biggest question — why the planes were dated — is still a mystery. The leading theory is that they marked a special occasion in a master carpenter's life. Period documentation has so far been unhelpful. The first documented purchase of tools from a professional planemaker comes from 1664, when a Swedish general ordered more than 200 planes from Amsterdam. The order makes no mention of carved planes. However, an invoice that accompanied the shipment describes two planes met gesneden mondt, "with carved escapement." If these kinds of planes were in fact unique to an individual carpenter, why was that not mentioned in the original order? According to Coolen, there is still much to be learned about the lives of early Dutch planemakers, as well as how they manufactured and sold planes, even where they sourced their materials from.4

A final word about dated Dutch planes: beware of fakes. Some time ago I bought a Dutch molding plane with a 17th century date carved on the side. When I got it home, I discovered it was actually made between 1865 and 1945. Additionally, as I subsequently learned, the Dutch didn't date molding planes in this way. In his book on Dutch planemakers, van der Sterre describes a similar fake "17th-century" plane. Thankfully, my plane cost a tiny fraction of what dated planes typically sell for. (And I learned a hard lesson about not rushing to buy a plane just because it seems like a good deal.) Consult someone knowledgeable before buying a dated plane. Reddit is useless for this kind of thing. The Rhykenologist Facebook group is a better place to start.

"And of the chests in my father’s workshop, in which the tools were stored, I write with a feeling that is almost reverence, so carefully kept were they, so very much the inviolable preserve of their owners. There, carefully ranged on end, each fitted side by side, was the long array of beech moulding planes; of beads, rebates, hollows, and rounds, all rubicund with repeated applications of linseed oil and mellow with the flight of years and much usage. In the middle lay the more cumbersome tools: the plough with its complement of steel blades (called irons) which, to avoid danger of rust, were kept carefully rolled in green baize; the sash fillister, the ovolo and lambstongue moulding planes, the long trueing plane and its companion the steel-faced smoother for finishing special surfaces. To us it was not merely that each tool bore the imprint of the owner’s name — T. Figg, A. Hyde, J. Saw or T. Ricketts — but that they were imbued with the owner’s personality. The hands had grasped the planes so long and so often that the surfaces had softened to the grip, yielding a smoothness of edge and slight undulations where the fingers were placed when at work. We could not see those tools without associating them with the owners, to whom they were as mute servants waiting the moment of need — the owner’s hands to select, adjust, propel and guide, the tools ever ready to respond to his well-directed efforts." — The Village Carpenter, Walter Rose (1937)

A quick note: Working Wooden Planes will be moving to a new, self-hosted platform sometime this year. The only change you’ll notice is that the newsletter archive will be at workingwoodenplanes.com instead of on Substack.

Happy new year!

—Abraham

Van der Sterre, Gerrit. Four Centuries of Dutch Planes and Planemakers. Primavera Pers, 2001.

Van der Sterre, 2001.

Coolen, Hein. "De Nederlandse Schaven in de 17e en 18e Eeuw: Stand van het Onderzoek en Nieuwe OntwikKelingen." Gildebrief, 2017.

Noorlander, A. "Meesters van de Krullen, Schaafmakers in de 18e Eeuw." Antiek, April 1972.

Coolen, 2017.

Surely joiners were between the carpenters and the cabinetmakers? (and able to use mitres and glue) Or were things different in the Low Countries?

"For instance, a house carpenter wasn't permitted to cut miters or make his own bedstead. In Bruges, Belgium, he wasn't even allowed to apply glue to his work." Damn right! Bring back the Guild privileges, I say. Time to teach those chippies a lesson :-)

...

I bought 'The Village Carpenter' by Walter Rose a couple of years ago and re-read it recently; it's a beautiful book. Interesting, informative and inspiring, but most of all a beautiful description of rural woodworking life ante bellum.