"They say a carpenter's known by his chips." — Jonathan Swift (1738)

Just before the turn of the 20th century, when steam-powered machinery dominated American manufacturing, the United States government paused in its relentless pursuit of economic growth and wondered if the erasure of countless hand tool production jobs was having unintended consequences. The report published as a result of that fleeting introspection has been long-forgotten, but inside of it is a precise picture of what it took to make a home with hand planes.

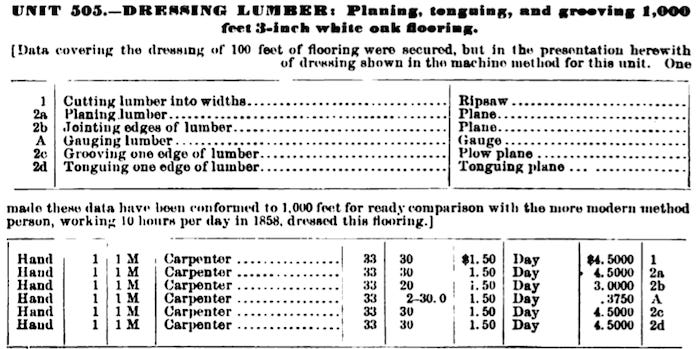

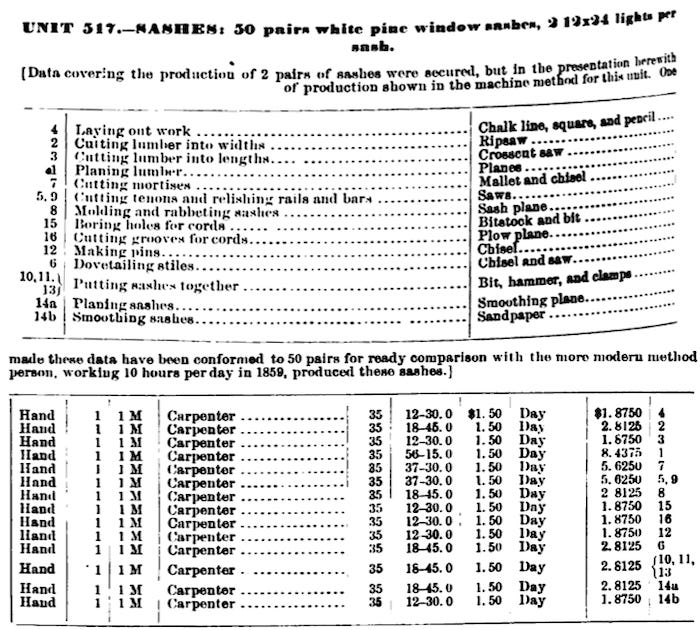

The report broke down each step needed to create, both by hand and machine, 672 products and services across 88 industries — including making wood flooring, ceilings, moulding, crown molding, mantles, window sashes, stairs, doors, and window frames. (Each table was published in two sections side-by-side, but I had to stack them on top of each other due to the narrow size of the newsletter.)

A single 35-year-old carpenter could make 1,000 feet of 4.5-inch yellow pine tongue and groove ceiling in four days, or about 250 feet in a 10-hour work day. A team of six people using steam-powered sawing and planing machines could do the same in less than an hour.

A 33-year-old carpenter could produce 1,000 feet of 3-inch white oak tongue and groove flooring in six 10-hour days. It took 30 hours alone just to rip the boards to size. A machine could do the same in nine minutes.

A 33-year-old carpenter could stick 1,000 feet of 3-inch mahogany molding in 80 hours. One thousand feet of molding is a ridiculous number — almost as tall as the Eiffel Tower or nearly as long as three American football fields, and more than enough for many homes. The 1,000 feet specified in each category was extrapolated from much smaller amounts that the craftsmen actually produced at a time, typically fewer than 200 feet. But the statisticians needed a larger number that could be compared with the huge amounts that machines were producing, sometimes up to 20,000 feet at a time.

It took three carpenters more than five days to produce 1,000 feet of 5-inch yellow pine ogee cornice molding. The labor cost for doing it by hand: $18.75. By machine: two people, 1 hour, $0.22.

Sash making (likely the subject of a future newsletter) is time-consuming. According to the data it would take 12 and a half days to make 50 sashes by hand. That seems pretty quick to me, but there are only two panes per sash. A window with lots of panes would take far longer.

The report, titled Hand and Machine Labor, came about following a recession in the mid-1880s. In 1894, Congress tasked the commissioner of labor to quantify the effect mechanization was having on labor issues. It was such a broad request that one economist called it "nothing short of a demand for a complete analysis of modern industrial society."1 Hand and Machine Labor took five years to complete and was so enormously complex (it topped 2,000 pages) that even the commissioner admitted there was no way to use the data to answer most of Congress' questions. It wasn't until recently that modern computing power allowed statisticians to conduct econometric analysis on it.2

As a window into how wood house products were made 170 years ago, the data is fascinating. If you're interested in hand tool woodworking, it's worth exploring. I think most of us would be woefully unable to keep pace with the workmen in the survey, even just jointing a floor board. But if you think you can beat their times, there's a good job waiting for you in 1859.

— Abraham

You can read the two volumes of Hand and Machine Labor at Google Books, here and here. I've excerpted some of the sections on dressing lumber by hand vs. machine, which you can download here.

Richmond Mayo-Smith, Review of Hand and Machine Labor. Political Science Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 1, 1900, pp. 153–55.

Jeremy Atack, Robert A. Margo, Paul W. Rhode. "'Automation' of Manufacturing in the Late Nineteenth Century: The Hand and Machine Labor Study." Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 2, 2019, pp. 51–70.

Could there be a matching study now, as many jobs involving routine and not-so-routine clerical and admin skills are likely to be eliminated by AI ? Thank you for flagging this study...and let us hope that in the ongoing move to automation, our history teaches us that we need to balance an appreciation by society of the value of skilled work for its social value, as well as its economic value.