Rhyken: Did the Ancient Greeks Really Have a Word for "Plane"?

Plus: A new video! And the rarity of cast steel in the 18th century

"The slanting sunbeams shone through the transparent shavings that flew before the steady plane." — George Eliot (1859)

Rhyken is commonly thought to be the ancient Greek's term for a woodworking plane. It was famously adopted by plane collectors in the 1970s, who coined the derivation rhykenology as the name for their new group, the British-American Rhykenology Society. Today the word lives on as the name of a well-known Facebook group and pops up occasionally in online woodworking forums.

But as far back as the mid 1960s, author and researcher William Goodman questioned the etymology of rhyken or rhykane.1 The Greek use of the word plane is found in only two places, both poems by Leonidas of Tarentum written in the third century B.C. The most famous translations of Leonidas come from the Scottish author William Roger Paton.

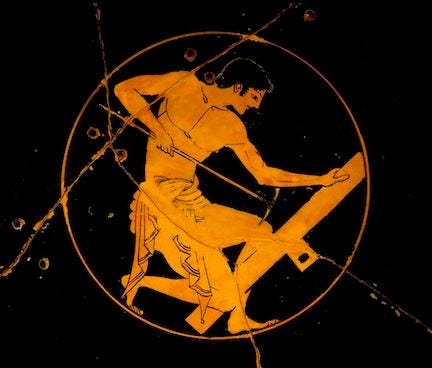

Leonidas was an epigrammatist, the writer of a type of short lyric poem. In the first poem, "Theris, the cunning worker, on abandoning his craft, dedicates to Pallas his straight cubit-rule, his stiff saw with curved handle, his bright axe and plane, and his revolving gimlet." (Pallas being another name for Athena, the goddess of craft.) Goodman points out that nothing about a wooden plane is "bright" (excepting the narrow edge of the blade), and suggests rhyken was more likely a type of tool with an open blade like a drawknife.

The second poem lists "the tools of the carpenter Leontichus, the grooved file, the plane, rapid devourer of wood, the line and ochre-box, the hammer lying next them that strikes with both ends, the rule stained with ochre, the drill-bow and rasp, and this heavy axe with its handle, the president of the craft." I love "rapid devourer of wood," but the word rhyken or rhykane doesn't actually appear in the original verse — Paton added it.

Goodman, who was a multi-lingual polymath, also looks into German and Latin translations of the two poems and comes to this conclusion:

"What probably happened, when translators came across some noun they were not quite sure about, is that they thought about tools which had not been mentioned and felt that a plane should come in somewhere. But the fact that the "heavy axe with its handle" was still described as the president of the craft suggests that the plane as we know it was not then present. Once true planes were in general use they would surely be regarded as the most important tools in a joiner’s kit."

Goodman points out that while rhyken may be suspect, the Greeks likely did invent the plane. The lack of a known word for the tool has more to do with prejudices regarding manual labor, according to Goodman, than lexicography. Plane shavings have been found in two coffins made by Greek craftsmen from the Hellenistic period.

William Goodman (1903-1993) was the author of the foundational work, The History of Woodworking Tools, and the reference book that still carries his name, Goodman's British Planemakers.

With my workshop 90% complete, I've finally been able to shoot a new video — the first in over a year. While looking into the history of cast steel, I was surprised to find that even though the English clockmaker Benjamin Huntsman had developed the modern cast steel process in the 1740s, it wasn't immediately adopted by English edge tool makers. According to Sheffield historian Kenneth Barraclough, there is no existing data on cast steel production in England in the 18th century. But the reports he compiled from visitors from Sweden, France and Germany who came to England to learn more about this incredible new type of steel give us a small view of what was going on.2

In 1774, a French engineer named Gabriel Jars found that reworked German-style blister steel was being used for everything from saws to files to knives. Shear steel was only made to order, for both England and export. And cast steel? "This steel is not in very general use; it only used for those items requiring a find polish. The best razor made from it, several penknives, the best steel chains, the springs of watches and small watchmakers' files."

Bengt Qvist Andersson, who traveled in England in 1766 and 1767, reported that English cutlers were still using blister steel, although Sheffield cutlers "to some extent" were using shear. Another Swede who visited in 1761 spoke with an ironmonger who expressed the mistaken attitude apparently many English edge tool makers had at the time. Cast steel, he said, gave "a uniform and good edge but not lasting," and "the consumption was, therefore, not large."

A few anecdotes are not a definitive account of all steel being used in the country. If anything, planemakers were probably at the forefront of demanding the best possible steel. According to Barraclough, Huntsman and his son after him were exporting cast steel to France, where they were selling it for maybe as much as 10 times the cost as in England. Perhaps French woodworkers were enjoying cast steel plane irons before the English were!

As always, thanks for subscribing.

— Abraham

Goodman, W. L. "The Woodworking Tools in The Greek Anthology - and reflections theron." Tools and Trades: The Journal of the Tool and Trades Historical Society, vol. 9, 1996.

Barraclough, Kenneth Charles. The Development Of The Early Steelmaking Processes, An Essay In The History Of Technology, Supplementary Volume. 1981. University of Sheffield. PhD dissertation.

Very interesting! And I also enjoyed the video -- very well presented. Please make more!

I have an 'oldish' Swedish iron with chipbreaker (Erik Anton Berg - Eskilstuna), wedge shaped in thickness. Now I have an urge to make a plane for it :-) I'm gonna have a closer look at it today and see what I can learn. I use mostly steel planes but it would be nice to make a long jointer for it. The wood would keep the weight down, too :-) I must investigate further...

Thanks!

So cool! Thanks for writing this up. I shared it with my watchmaker friend.