"When you hold a tool, your fingers form an intimate bond between you and the tool. It is a marriage of intellect and an inanimate object. Suddenly the tool comes alive." — R. J. DeCristoforo (1977)

When it comes to comparing wooden planes and power tools, molding planes are nearly always superior to their corded counterparts. They're a fraction of the cost of a router. Just a few rounds and hollows take the place of — and far exceed — expensive router bits. Unlike a router, molding planes leave a near-perfect finish, no sanding required. They’re also a way for both beginner and advanced woodworkers to show off their creativity. “You are a craftsman,” planemaker Matthew Bickford writes, “and these tools will allow you to prove it again and again.”1 It’s no wonder they’ve been around for at least 2,000 years.

First, you're going to need a way to hold the piece of wood you'll be using for your molding. Steve Hay shows off a sticking board made with two pieces of plywood and a few screws. Screws are preferable to a fixed stop because you can raise and lower them depending on the height of your molding. (If you want something more substantial, James Wright makes a sticking board with plane stops.)

Now that your workpiece is secure, let's start with the basics. If you need a refresher on what molding planes are and what they can do, Joshua Farnsworth explains rounds, hollows (and what their numbers mean), and complex molding planes. Shannon Rogers at Renaissance Woodworker also has a good explainer, as does Paul Sellers.

Staying with the basics for a moment, Walter Ambrosch at Dusty Splinters has step-by-step instructions on how to set the iron on your molding plane.

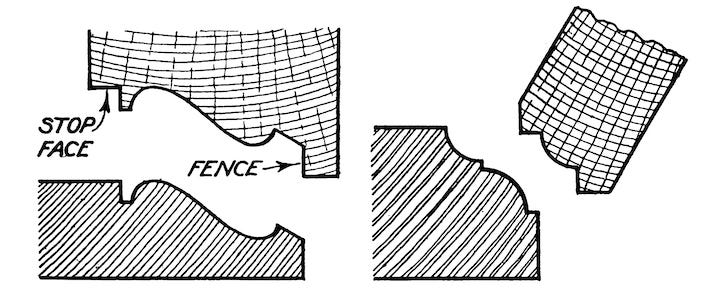

There are two different methods for sticking moldings. One is to use a complex molding plane. The integrated fence and depth stop make it easy to produce a consistent profile. But as Charles Hayward shows on the right below, that fence and stop limit the versatility of this type of plane.

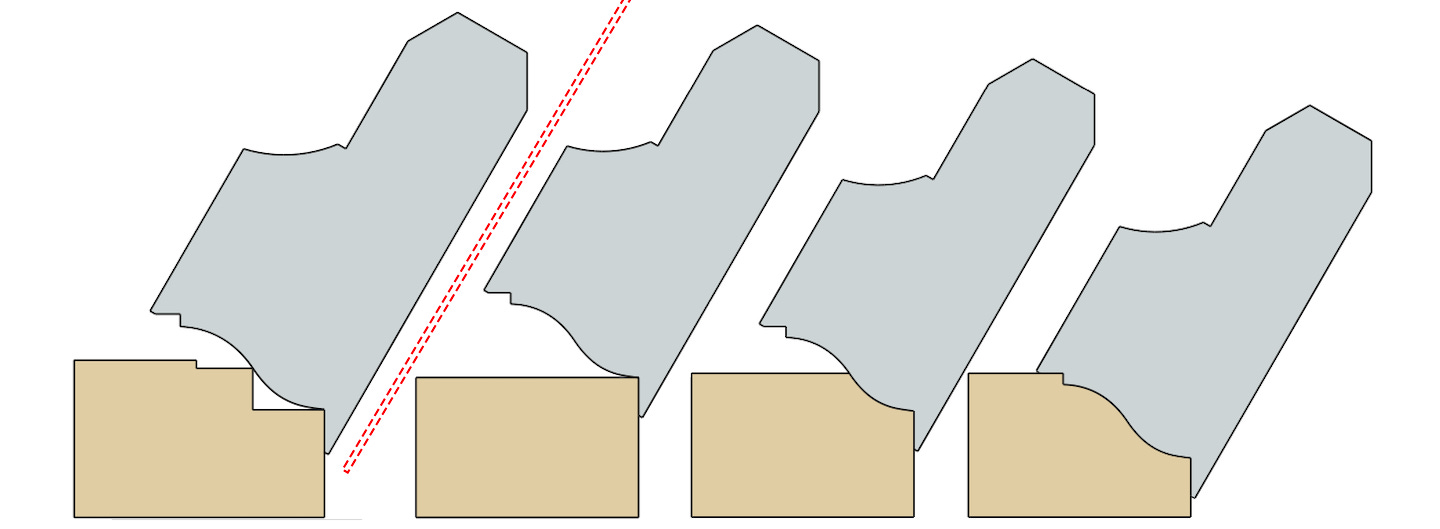

As Matthew Bickford illustrates in his book Mouldings in Practice (a must-have resource), you can either plane a series of rabbets for the iron to sit in (far left), or you can rely on the integrated fence (right). Using just the fence is the most time-consuming and labor-intensive. One of the trickiest parts to using a plane with a dedicated profile is holding it at the correct angle. Bill Anderson explains spring lines — which help you maintain the angle — and how to determine the depth the plane cuts. He also demonstrates how to set up and hold the plane. (Graham Blackburn has more on spring lines.) Bickford shows off some of his molding planes here and here.

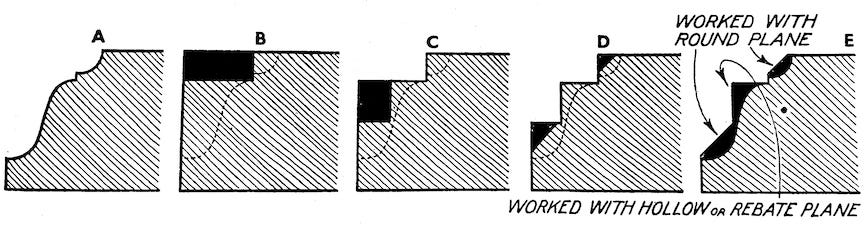

The second method to sticking moldings is to use hollows and rounds. This is where your personal creativity comes in. Hollows and rounds are used in conjunction with a rabbet plane. (You can often buy those three planes for the cost of a nice complex molding plane.) A rabbet plane removes most of the waste, but more importantly, it creates a foundation for a hollow or round to sit in or on, as Hayward illustrates.

Bob Rozaieski demonstrates how simple the process is.

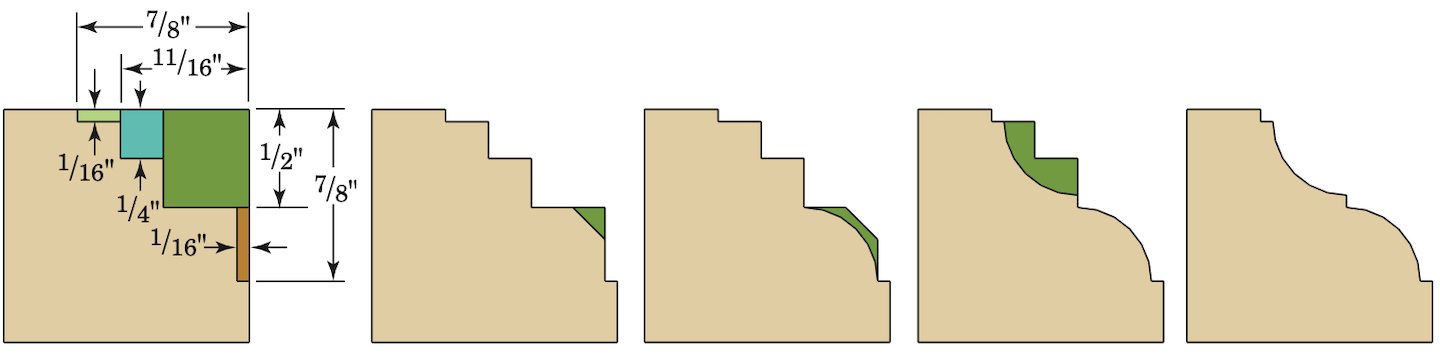

By varying the height and width of each rabbet, and changing the size of the hollow and round, you can create endless variations. Below, Bickford shows how the rabbets are cut in order, starting with dark green, then brown, blue, and light green, followed by a number six hollow and round. This is one of the basic profiles these planes can make. In his book, Bickford illustrates how to make dozens of other complex profiles.

Simon James shows just how versatile rounds and hollows can be in creating large profiles, much larger than you could make with most dedicated molding planes. He starts by making a cove using a jack, rabbet, and a number 12 round plane. His second video combines that cove with an ovolo. HNT Gordon & Co. also has a good video on rounds and hollows, which includes using a snipe bill plane to start.

Beading planes are the oft-forgotten molding plane. Below, Joshua Farnsworth shows how to add a decorative bead to a shiplap joint. Walter Ambrosch also has a deep dive into beading planes.

Of course, it's likely you'll need to tune up your molding plane. PJT Furniture has a three-part series on restoring them. In this video, he shows how to use sandpaper to restore the sole’s profile. Don't miss the third video, where he shows how to reshape the iron to match the new shape of the sole.

Sharpening either a round or hollow iron or a complex molding iron seems intimidating. James Wright shows how easy it is. Paul Sellers and Shannon Rogers both have more on sharpening molding irons.

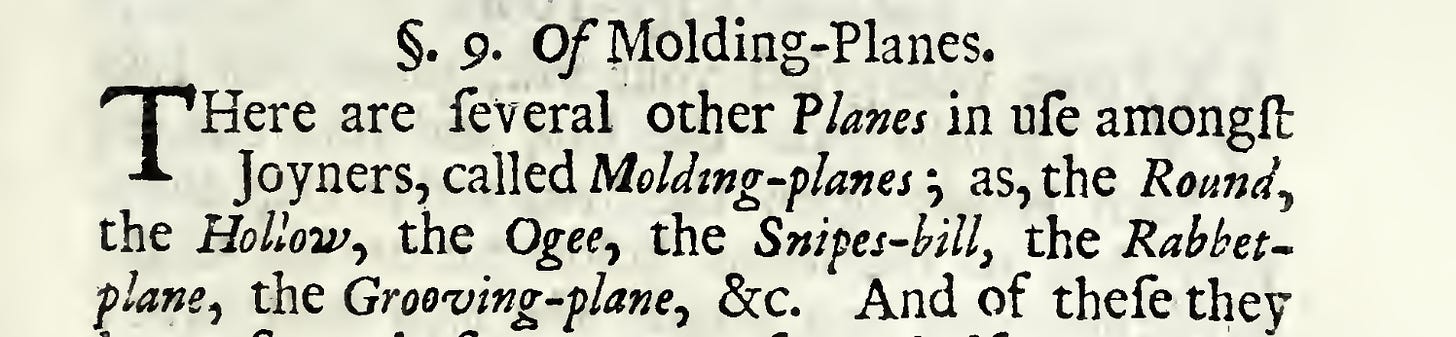

As for the spelling of molding vs. moulding, “mold” in all its various uses is a fairly recent Americanization of the British spelling “mould.” The word moulding when used to describe architectural elements has its roots in Middle English. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first known reference to moldings used in woodworking comes from our old friend Joseph Moxon in England in the late 1600s. However, while he used “mould” when explaining bricklaying methods, he used the so-called American spelling when describing planes.

I'm remodeling our house, room by room, and when I opened up the wall this door sits in a few weeks ago, I realized something: The things we make are a conversation with future makers. I mean this literally. Your creative voice speaks through time, explaining your skills and knowledge, imagination and artistry, to future generations.

The framing on this doorway is horrifying. Rafters in the attic are braced just above this door. That means the 2x4s on the left side and the cheapo 1/2 inch door jamb are carrying the weight of the roof. It's a miracle the roof isn't sagging. The parts of this house built in the 1930s have their own issues. But this door is typical for the part constructed in the late 1970s. Every wall I open up, it's like the people who built this have stepped through a portal and are standing next to me, telling me how they didn't know what they were doing, how they didn't take the time to learn more.

It's not that the work must be flawless. Our mistakes — and how we fix them, hide them, adapt to them — are all part of this one-way conversation. As the writer and designer Kat Roberts puts it, "Craft involves an awareness of a human having been responsible for an object’s creation, as if the maker’s presence never entirely leaves the object."

Framing a door doesn't feel like "craft," but making something right, something fundamental, feeds something good inside me. I rebuilt the doorway like it should be: king studs, trimmers, cripples, 2x10s for the header. Now the weight of the roof is transferred around the door and down into the floor joists. The doorway is plumb and level, ready for the door I'll be making myself. I hope the next person who tears open this wall hears what I am saying.

— Abraham

Bickford, Matthew Sheldon. Mouldings in Practice. Lost Art Press, 2012.