The craft of commercial wood planemaking in the English-speaking world stretches out over three centuries and encompasses more than 2,400 British and 4,000 American makers. While biographical data is unknown in some cases, all others have been identified as men. Surely a daughter, a wife, an un-recorded apprentice trained and worked alongside one of those craftsmen? Decades of research done on early tool makers has found that women's contributions at the bench were simply not recorded. But they were sometimes a core part of planemaking operations, many times running the business and collaborating with or overseeing journeymen after the death of their husband.

The practice dates back to the earliest days of commercial planemaking. When London's first major plane producer Robert Wooding died in 1728, his wife Ann oversaw the business until her own death in 1739. Anne took on several apprentices, including Thomas Phillipson. When Phillipson died in 1761, his wife Susannah carried on as proprietor for another 14 years.1 Trade guilds in 18th century England strictly regulated who worked in various professions and who they could take on as apprentices. Surprisingly, sisters Sarah and Mary Flight were apprenticed to two different plane makers in London in 1743. As the two women did not go on to become planemakers it's likely that they were trained in business management.2

It must have been a staggering amount of work, running both a company and a household, which itself would have been a full-time job. Plus there was the toll that may have come from breaking established norms in strongly patriarchal societies. As historian Sharon M. Harris notes, "Women who were forced into or chose nontraditional roles bore double burdens: they carried the entire responsibility for their own or their family's survival, and they faced social disparagement and sometimes ostracism for having the courage to do so."3

Here are a few of the women who took on that role. (This is not meant to be a comprehensive list; these are only names that I have encountered.)

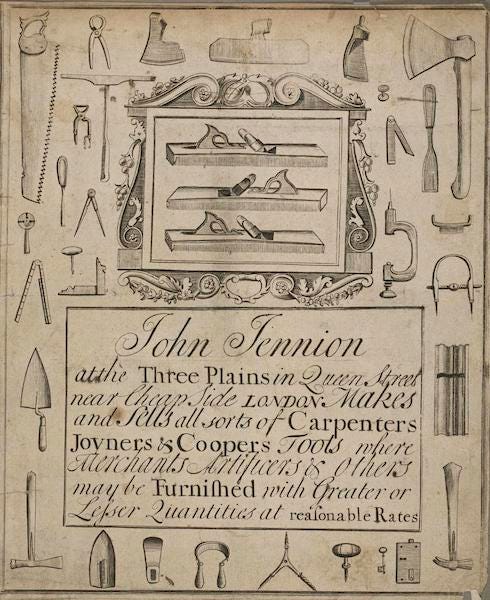

England: Ann Wooding (Robert Wooding), London, 1728-1739. Anna Jennion (John Jennion), London, 1757-1778. Susannah Phillipson (Thomas Phillipson), London, 1761-1775. (Unknown first name) Moodey (Thomas Moodey), Birmingham, <1773-1776. Elizabeth Hathersich (George Hathersich), Manchester, 1845-1851. Martha Barton (Stephen Barton), Bristol, 1855-1873.4

Canada: (Unknown first name) Wallace (Alex Wallace), Montreal, 1858-1862. Edesse Nicol (Sem Dalpe), Roxton Pond, Quebec, ?-1895. Anna Monty (Adelard Monty) Roxton Pond, Quebec, 1929-?5

United States: Ester/Esther Walker (Jesse Walker), Cincinnati, Ohio, 1829-1831? Catharine Seybold (Emanuel F. Seybold), Cincinnati, Ohio, 1853-1855. Rachel Brooks (William Brooks), Philadelphia, Pa. 1808-1813. Margaret Napier (Thomas Napier), Philadelphia, Pa. 1813-1822? Charlotte White (Israel White), Philadelphia, Pa., 1839-1845. (She remarried in 1845 as Charlotte Burnett and continued to work in planemaking 1845-?) Mary Duke wasn’t a planemaker but she marked planes with the stamp of the hardware store she co-owned with William Glenn, Philadelphia, Pa. 1837-1840.6

Contemporary commercial planemakers are still predominantly men. But what about people who make them as part of their profession? There's at least one woman I know of: furniture maker Jennifer Anderson. She studied under James Krenov and Wendy Maruyama and currently teaches at colleges in Southern California, including a class on plane making at Palomar College in San Marcos.

- Abraham

Since 2020 Reinhard Pascher has been publishing his research on Austrian planemakers at Hobel Austria. He recently launched @hobelaustria on Instagram. Definitely worth a visit.

I posted a new video this week where I look at at 18th and 19th planemaking design styles.

Jane Rees. Goodman’s British Planemakers. 4th ed., Astragal Press, 2020.

Don and Anne Wing. Early Planemakers of England: Recent Discoveries in the Tallow Chandlers and the Joiners Companies. Mechanick’s Workbench, 2005.

Sharon M. Harris, ed. American Women Writers to 1800. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Rees, 2019.

Gary Paul Lehmann. "The Distaff Side of Planemaking Recognized in Canadian Guide." The Chronicle, vol. 55, no. 4, 2002; Alan G. Bates; Jacques Heroux. Re: A trip to Roxton Pond. OldTools. 30 Sept. 1996.

Elliot M. Sayward. "Notes & Queries." Plane Talk, vol. 5, no. 2; Warren E. Roberts. “Planemaking in the United States: The Cartography of a Craft.” Material Culture, vol. 18, no. 3, 1986; Thomas Napier: The Scottish Connection. Early American Industries Association, 1986; Carl Bopp. "From the Distaff Side: Some Female Entrepreneurs." The Chronicle, vol. 57, no. 3, 2004; Emil and Martyl Pollak. A Guide to the Makers of American Wooden Planes. 4th ed. Astragal Press, 2001.