What ancient hand tools do to our emotions

Plus: The plane that joined a town together, and learn how to draw a jack plane in Telugu

"Worn Out" — Cause of death on Ohio planemaker James Starr's death certificate (1872)

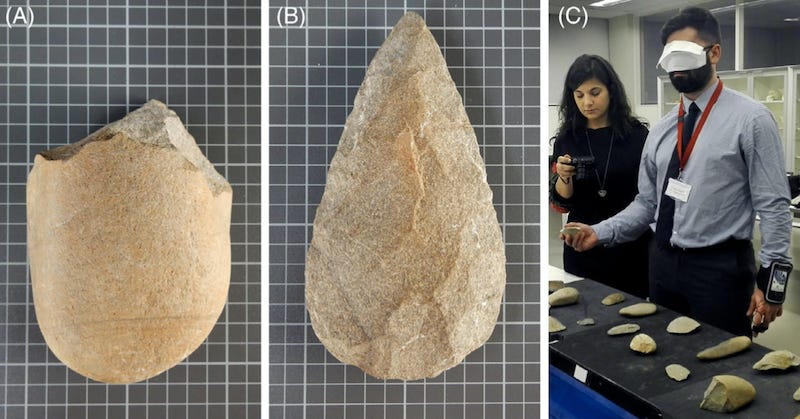

Somewhere around 2.6 million years ago, our earliest ancestors smashed rocks together and made our first hand tools. These Oldowan choppers are the most ancient of technologies, and incredibly, modern humans seem to have a spontaneous emotional reaction when we handle them.

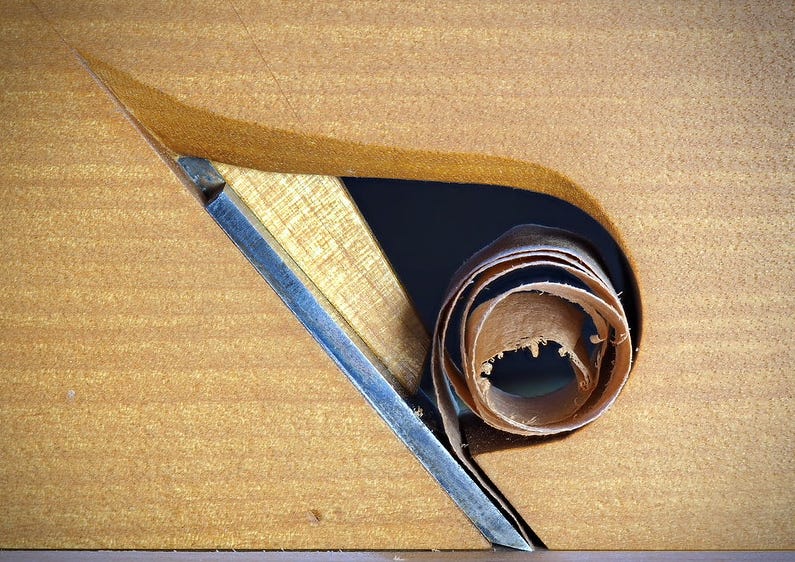

Toolmaking forever altered human evolution. Choppers take years of practice to learn to make. That process created new neural pathways in our brains that we would eventually use to develop language and complex societies. Tool use became such an integral part of us that when we pick up a tool today our brains perceive it as a literal extension of the body, as if our hand had suddenly grown to the same length as the tool.1

In a series of studies over the last few years, researchers monitored people's electrodermal activity—tiny changes to the skin that indicate an emotional response—as they handled stone tools. Even if you don't feel an emotion, electrodermal activity can show that your brain is still reacting. Oldowan tools elicited the strongest emotional response. Acheulean handaxes, which gradually began replacing choppers around 1.6 million years ago, created the second strongest reaction. Stone scrapers, made between 50,000 and 500,000 years ago, came in third.2

While electrodermal activity is interesting, it doesn't show what type of emotion is being produced. And the studies' authors point out there are several ways to interpret the results. I like their theory that the emotional response is one of recognition. We used choppers for more than 40,000 generations, a lineage of toolmakers molding and being molding by technology. We may have moved on to touchscreens, but sometimes, somewhere in the depths of our hominin brains, a tool feels just right, like we were born to use it.

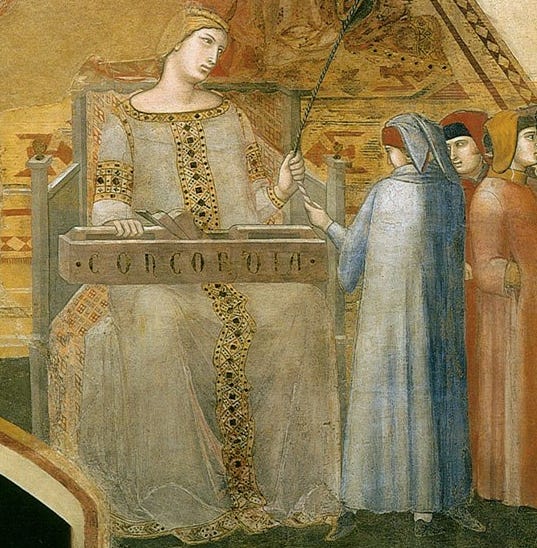

The Allegory of Good and Bad Government is a series of frescos painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Italian town of Siena between 1338 and 1339. The paintings are a hodgepodge of metaphors representing the moral principles Lorenzetti thought should underpin a healthy society. In one of the frescos, a rope passes from the scales of justice through the hand of a woman who is seated with a wooden jointer in her lap, and then into a procession of men representing the city's officials. The plane is marked "Concordia," or harmony. What makes the Concordia plane interesting is that it's one of the first known representations of a long jointer. It must have been a well-established tool at this point if people understood it was plane used to join things together (as opposed to flattening or smoothing). Why it has two wedges is unknown.3

And now for something completely different: How to draw a wooden jack plane in Telugu.

The newsletter is back for 2023! Thank you for sticking around during my hiatus.

— Abraham

our brains perceive: Maravita, Angelo and Atsushi Iriki. "Tools for the body (schema)." Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 8, no 2, pp. 79-86, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.008.

Bruner, Emiliano, et al. "Cognitive archeology, body cognition, and hand–tool interaction." Progress in Brain Research, vol. 238, pp. 325-345, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.06.013. Fedato, Annapaola, et al. "Electrodermal activity during Lower Paleolithic stone tool handling." American Journal of Human Biology, vol. 31, no. 5, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23279. See also: Silva-Gago, María, et al. "Not a matter of shape: The influence of tool characteristics on electrodermal activity in response to haptic exploration of Lower Paleolithic tools.” American Journal of Human Biology, vol. 34, no. 2, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23612.

first known: Greber, Josef M. Die Geschichte Des Hobels. Translated by Seth W. Burchard. Early American Industries Association, 1991.

classic subjects, Thanks again!